Jordan Oelke – TU Dresden (Human Geographer)

Andrzej Jarynowski – FU Berlin (Epizootiologist)

Vitaly Belik – FU Berlin (Data Scientist)

Frank Meyer – TU Dresden (Human Geographer)

Shortly after midnight on Thursday the 20th of July 2023, a low quality 16 second-video taken from the side of a roadway outside the German village of Kleinmachnow on the border between the German capital of Berlin and the Bundesland Brandenburg was posted to twitter. This video seemed to show a large mammalian body scrummaging in the bushes with only the animal’s side, back and neck/ears visible. The question arose whether this was a lioness, and news outlets from Germany to India and Britain picked up the story. The events to follow would reveal the traditional media’s influence on social life, when a social media post is picked up and sensationalized, fear is spread and security efforts are employed as a response to the public concern.

Let’s take a look at the role the media played (e.g,. by using clickbait-techniques or fueling emotions) using a mixed-method (quantitative and qualitative) approach regarding the narrative of security and responsiveness in the face of a ‘dangerous lion’. This narrative subsequently generated viewership and advertising revenue before later transitioning to peace (with a bit of humour) having been restored when the ‘lioness’ was found out, to in fact be a wild boar.

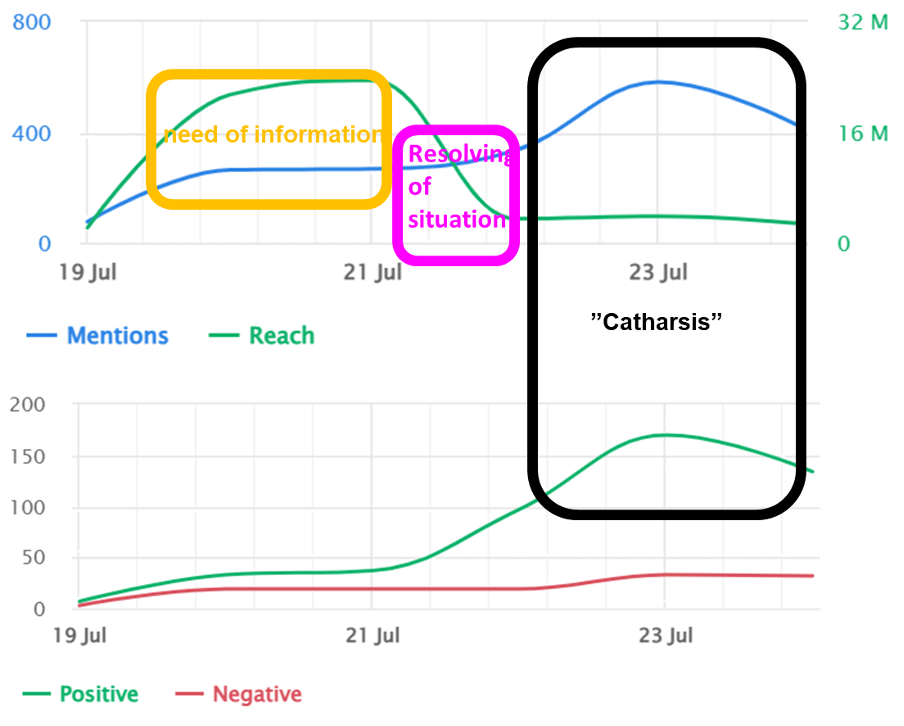

We gathered the demand of information (Google Trends) in Berlin and Brandenburg on the topic of the ‘Lion’ (regional but also international audiences, especially in the metropolis), and the supply of information (Brand24) – 2159 mentions in social and traditional media with a given keyword “Löwe” (due to the major discussion taking place in German among citizens). Additionally, Allan, Adam and Carter (2000) Environmental Risks and the Media, help guide the qualitative media discourse analysis to match certain media engagements and representations with spikes in the time series of information flow (and its sentiment in case of mentions) to understand the social dynamics of the issue.

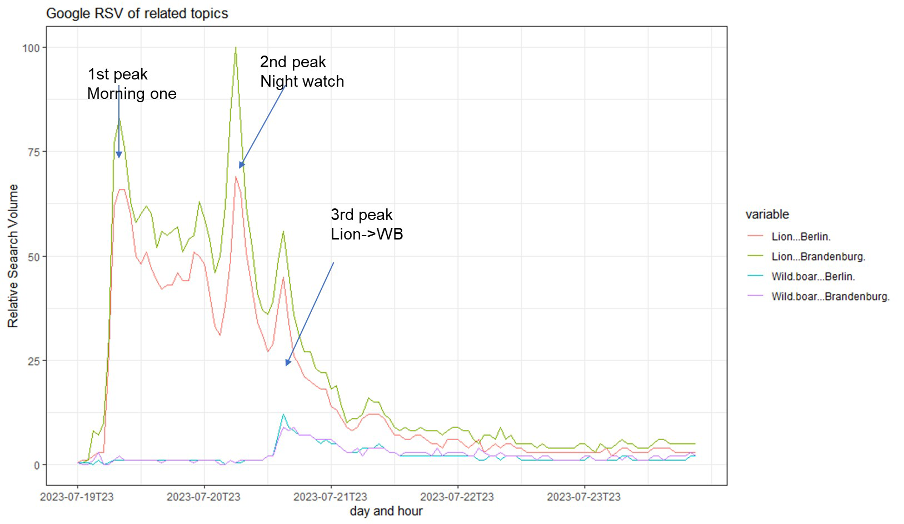

The 1st peak concerning the emergence of and awareness regarding the threat occurs around 7am on July 20th, when people woke up and checked social media before work, or heard the news from a personal contact, and later inquired further into the situation about the alleged lion. In the meantime, crisis management teams made up of police, military, veterinary officers, and citizens (between 100-200 personnel) split into units to handle the situation. The story grew as more disinformation spread about the lion having chased after and/or consumed a wild boar. The mayor of Kleinmachnow, Michael Grubert updated citizens and spectators in his largest press conference ever on July 20th, officially speaking of the threatening ‘lioness’ roaming at large. The media interest then dropped and levelled out, as news reached the bigger metropolis of Berlin. A concern was apparently tied to the ‘green’ wildlife corridors in the city as wild boars or lions may move between there and Brandenburg via the Grunewald-forest. A correspondent for the English newspaper “The Guardian” provided an analytical-voice to the situation, detailing the forest canopies in Grunewald at the edge of the village to be an ideal ‘jungle’ substitute to hide and that wild boars and other wildlife would provide nutritious and abundant food sources – thus, building on the misinformation.

The 2nd peak occurred around 5am on July 21st and was at its peak when people were eagerly waiting for the resolution of the issue during the sleepless night of July 20th and into the morning after. The threat to other potential food sources, specifically pets, as ‘ideal lion food’ were among the major subjects of focus in the media.

Graph 3 (bottom): Emotions in social and traditional media (Source: Brand 24)

The values in graphs 2 and 3 were provided on a daily basis and smoothened. In graph 3, the sentiment shows the amount of charged emotions in social and traditional media posts on the internet. The increased attention of the general public (seen in graph 1) as well as traditional (high reach) and social media continued as the lioness had still not been found (which, according to the data, carried a high frequency of mentions and negative corresponding emotions).

A discourse about securing a solution to effectively reduce the wild boar population, viewed to be a threat to local traffic and residents’ gardens was started online about ‘wild boar(s)’, as according to the mayor of Kleinmachnow, people were spreading disinformation that the lion(ess) may have been released by the city as a possible new wild boar hunting system. He explicitly stated that “we are still trying to do it normally (hunting of wild boars) and will not set up a Serengeti Park in order to be able to solve the wild boar problem. But it is a serious situation“ (Global News on July 20th, 2023). This perception was increased because boars are the main host of the African Swine Fever virus (ASF; we will touch more on this). Native predators naturally manage other wild animal populations but, as we can see with the return of wolves in Brandenburg and Saxony, many other issues follow such as wolf attacks on livestock and hunter-wolf confrontations.

The interest in the alleged lion continued until around 11AM on July 21st with some level of negative emotion, but without signs of panic. Although some social media users (i.e hunters) were baffled and clearly saw a wild boar, the event had already taken on the emotional and pressure charged atmosphere while Berlin, Germany and other parts of the world looked on, expecting to find a lion and to remove the threat. The large police force was represented in the media through the voice of one interviewed citizen, as providing a sense of control and security. Therefore also justifying the 30 hours straight search that required large financial resources to conduct such an investigation, with infrared cameras, combat weapons, etc (July 22nd, 2023, DW News). Consequently, the streets were reported to remain ‘more quiet than usual’ in response to the ‘stay at home order’.

The demand for news (see graph 1) increased for the third time around 12AM on July 21st. Around this time, the investigation of the search, an examination of faeces/stool samples, and a deep analysis of video footage conducted by an expert determined that the Berlin lioness was, in fact, most likely a wild boar. This was announced by the police chief Peter Foitzik and the town mayor, who held up a picture showing the visual differences between a wild boar and a lion in front of an audience of reporters and citizens, and was accompanied by an official press release on the town’s website.

The 3rd and final peak started around 12 pm on July 21st as a wild boar supplanted the lioness, becoming the protagonist. However, graphs 2 and 3 show that the online-mentions across both forms of media are still high despite the decrease of news releases. Here, a positive emotion observed in social media (graph 3) could correspond to optimism and humour and irony appearing in the discourse. This is likely caused by social media carrying the weight as people’s mood started to change from worry to amusement. Panic died down as the situation was resolved. The media circus’ conclusion emerged in the shape of memes and satirical discussions on social media at the expense of the involved authorities during the weekend of July 22nd and 23rd.

The social media event of a potential lion spotted at the roadside spiked interest and concern for oneself and their loved ones. When sensationalised by the traditional media, such an event’s spread reveals an agenda of highlighting phenomenon that, although far-fetched, is in demand and has potential for far-reaching viewership.

Alternative voices with knowledge on a topic of concern must seek support through social media engagement: Some hunters, knowing that the lion was a wild boar from the beginning, but did not have the same responses and exposure on social media. Meanwhile, in the aftermath of the ‘discovery’ of the lion as a wild boar, one hunting school offered to teach interested people how to distinguish between wild boars and lions. Although sentiments of disbelief or disappointment existed in finding out that there was no lion at all, as revealed through informal surveys by news reporters, a sentiment of calmness returned, likely due to the normalised presence of wild boars in and around the region, which didn’t require a feeling of shock. The state of security ended and citizens were seen walking around freely without police presence in forests or at road stops. One could have avoided the state of security and hundreds of thousands of Euros invested to pay police, military, etc had the expertise of hunters been asked for prior to search teams’ deployment.